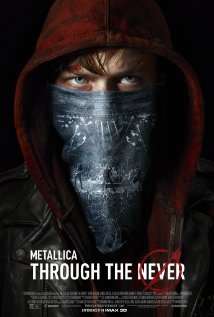

While Metallica plays to a sold-out crowd, hapless young

roadie Trip (Dane DeHaan) is sent across town to retrieve a mystery item from a

disabled truck driver. Along the way, he undergoes a nightmarish journey and

must escape the clutches of a mob led by a sinister masked Horseman.

Directed by Nimrod Antal, Through

the Never is a tale of two movies. As a concert film, it works wonderfully

in showcasing that the 50ish rockers still have it. The band plays its

A-material (“Master of Puppets,” “One,” “Creeping Death,” etc.) with aplomb and

looks and sounds good doing it. You don’t even need to be a Metallica fan

(though it certainly helps) to appreciate it, either: the band plays with enough

infectious energy to bring out the headbanger in all of us. Were this the

entirety of the proceedings, Through the

Never would be a solid hit.

As a concept film, however, it is a dismal failure. First and

foremost, its concept is poorly defined. The mob battles the cops, suggesting a

vaguely anarchist agenda, but don’t go looking for a coherent philosophical vision

here. Nothing in Trip’s journey makes a lick of sense, and that appears to be

very much by design. In addition, while there are few dull moments, the utter

stupidity and lack of purpose make all the flying fists and fire difficult to

enjoy even on a visceral level. Every cool-looking visual serves as a reminder

of how little substance there is behind the style.

Alas, because of the constant alternation between the two

threads, one must take the bad with the good. That’s a real shame because if

the band had either excised Trip’s odyssey entirely or actually bothered to flesh

it out, we would be looking at The Wall

for the Millennial Generation. Instead, we are left with a frustratingly

pointless mess with an above-average soundtrack (which, perplexingly, does NOT

include the title song).

6.25/10