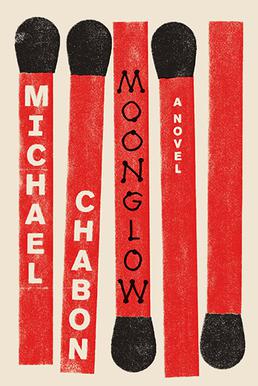

In this

fictionalized memoir, Michael Chabon revisits the beginning of his writing

career and the end of his grandfather’s life. The dying man recounts his

childhood in Philadelphia, his lifelong interest in rocketry and space

exploration, his World War II service spent trying and failing to capture Nazi

scientist Wernher von Braun (who becomes something of an arch nemesis), his

troubled marriage to an unstable French refugee with a young daughter, his

stint in prison, and his late-life romance with a widowed painter.

There was

a time when Michael Chabon’s books were as purposefully plotted and paced as

they were stylistically evocative, but 2012’s meandering, self-indulgent

(though still colorful) Telegraph Avenue

put an end to that equilibrium. Moonglow,

with its overlapping plotlines and nonlinear treatment of time, does not

restore it, but it does strike other balances: between intimate family history

and world-altering events, between touchingly poignant sincerity and crassly

irreverent humor, and between tragedy and triumph.

As with

previous works, Chabon excels at bringing people and places to life. Though neither

grandparent is named, both emerge as complex, fully realized characters. The

grandfather’s capacity for violence is weighed against his commitment to family

and obsession with rocketry while the grandmother’s theatrical gifts mask a

tortured past. There is also a rakish, eye-patch wearing pool-hustling ex-rabbi

uncle for good measure. Though the narrative moves around a lot – back and

forth between Philadelphia, Europe, New Jersey, and Florida – each setting is

clearly and convincingly rendered (As a native of northern New Jersey, I got a

kick out of reading about the grandmother’s performances at the Paper Mill

Playhouse).

For all of

these virtues, Moonglow’s narrative

structure is nothing short of maddening. The three main plotlines – the grandparents’

love story, the grandfather’s war experiences, and the grandfather’s retirement

years – are constantly jockeying for the reader’s attention, and more often

than not, they interrupt rather than complement one another. Going from a

soldier’s haunting recollection of the horrors of war to a lurid description of

an old man’s sexual appetites to a child’s eye view of obscure card games

creates a kind of mood whiplash that does the novel a disservice. While this

digression-laden, fragmentary approach is not without purpose – it evokes the

way that Chabon himself probably heard some of these tales – Moonglow definitely could have

benefitted from a more conventional structure.

Moonglow is not quite a return to form, and

it falls short of both Chabon’s earlier works as well as the gold standard of

family sagas that is Jeffrey Eugenides’s Middlesex.

However, it is still a bold and touching blend of fact and fiction, one worth

cutting through the structural clutter to explore.

7.75/10

No comments:

Post a Comment