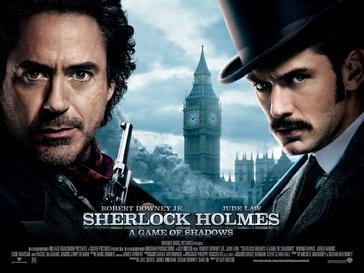

At the end of the 19th century, a series of bombings puts France and Germany on the brink of war. Though the blame falls on anarchists, madly brilliant English detective Sherlock Holmes (Robert Downey Jr.) believes Professor James Moriarty (Jared Harris) is behind it all. Unfortunately, the meticulous Moriarty leaves no damning evidence, and so it is up to Holmes to uncover and foil his plot. He is assisted by his even more eccentric brother, Mycroft (Stephen Fry), a Gypsy fortuneteller caught in the crossfire (Noomi Rapace), and, reluctantly, his newly-married partner, Dr. John Watson (Jude Law).

Set after 2009’s Sherlock Holmes, Guy Ritchie’s follow-up keeps its predecessor’s suspense and humor but jettisons the complexity of the plot. Whether that is a net gain or a net loss will depend on your expectations. Personally, I found that while the 2009 outing aimed too high, A Game of Shadows aims too low. Moriarty’s machinations are fairly transparent, and the bits of mystery regarding the identity of the assassin feel shoehorned in.

Fortunately, plotting issues do not detract from the film’s brisk pace and overall sense of fun. There are assassins at seemingly every turn, and Holmes’ calculating martial arts mastery is utilized again to good effect. On the other hand, the use of new-for-the-time weaponry such as machine pistols and Ritchie’s affinity for Max Payne-style bullet time sequences do not sync well with the film’s otherwise Victorian character.

Downey again anchors this film, portraying Holmes as a highly talented madman. He nails both the accent and the idiosyncrasies and performs with gusto. Law’s Watson is decidedly less stiff this time around, though he’s still very much the yin (marksmanship, medical skills, reason) to Holmes’ yang (deductive ability, esoteric knowledge, insanity). Of the new additions to the cast, Fry fares best here. His Mycroft is essentially an older Sherlock turned up to 11, a dry-witted loon who somehow commands the respect of the English government. Harris gives Moriarty a ruthless edge, but one cannot help but feel that he is wrong for the part. Anthony Hopkins or even the rumored Brad Pitt would have been a more interesting choice. And while Rapace gets to do plenty of running around, her dialogue, screen time, and overall contributions are minimal for such a supposedly important character. The erstwhile Lisbeth Salander deserves a better showcase for abilities.

A Game of Shadows draws heavily from Arthur Conan Doyle’s "The Final Problem" and incorporates some breathtaking shots of Switzerland’s iconic Reichenbach Falls. While that might make the ending seem like a forgone conclusion, viewers will do well to remember that in the world of Sherlock Holmes, nothing is as it seems.

8/10