In December 1979, retired Wichita police officer Gunther Fahnstiel accidently backs over a stranger with an RV. He finds a large cache of money alongside the body and decides to stow it away for safe keeping. Ten years later, 77-year-old Gunther breaks out of his nursing home in an effort to find his hidden money. He is pursued by his wife, his ex-bouncer stepson, a former police colleague, and a greedy, philandering real estate developer. As Gunther scans his memory to remember the hiding place, an incident from his police days in the early 1950s threatens to derail him.

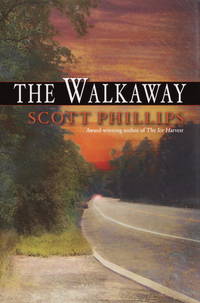

Scott Phillips’ 2003 follow-up to The Ice Harvest retains much of the former’s dark humor and imbues it with a sense of the past. On the surface, the tonal shifts are hard to detect. After all, The Walkway, like its predecessor offers an unlikely protagonist to get behind (a senile ex-cop instead of a scheming drunk lawyer), gleefully bathes itself in sleaze (a prostitution ring here instead of a strip club), and tempers its James M. Cain like noir sensibilities with some good old fashioned Midwestern idiocy. However, whereas The Ice Harvest’s Charlie Arglist seems to live very much for the moment, Gunther is clearly a man with some demons.

In this sense, Gunther has quite a bit in common with the book’s antagonist, crooked 1950s G.I. Wayne Ogden. Just as Gunther is willing to do whatever it takes to recover his lost loot (and, one can assume, his dignity), Ogden is hell-bent on getting revenge on his estranged wife, even going as far as to slip back into town using the name of his commanding officer. That the two cause untold pain and suffering to those around them despite their seemingly opposite alignment reinforces one of the untold rules of noir: there are no heroes.

While The Walkaway has a lot going for it, its structure is a mess. Time movements (between 1952 and 1979) are frequent and follow no fixed pattern. There are also no fewer than half a dozen focal characters (on top of plenty of supporting players – the names pile up), and sometimes, the perspective will shift within a chapter. This disorientation makes sense from Gunther’s point of view (he is battling senility, after all), but for a reader, it’s pure frustration.

Phillips also has a penchant for downer endings. While this too can be taken as a hallmark of the noir genre, the sense of futility in those final pages can really make you feel cheated. Then again, if The Ice Harvest didn’t end this way, The Walkaway would probably have no reason for being (and would, at the very least, have a different title).

All told, Phillips tells an interesting tale, but his work is still too slight and, in terms of structure, too sloppy to leave us craving more.

7.25/10

No comments:

Post a Comment