When her father is murdered by hired hand Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin), 14-year-old Mattie Ross (Halie Steinfeld) hires notorious U.S. Marshal Reuben “Rooster” Cogburn (Jeff Bridges), a one-eyed drunk of notoriously mean temperament, to help bring Chaney to justice. They form an uneasy alliance with La Boeuf (Matt Damon), a proud Texas Ranger who has been pursuing Chaney in connection with another crime.

Remaking a film whose lead actor won an Oscar for the role seems like a tall order, but for the Coen Brothers, anything cinematic is possible. The 1969 version of True Grit featured arguably the best performance of John Wayne’s career and supporting turns by the likes of Robert Duvall and Dennis Hopper. Nevertheless, the 2010 version surpasses it in every way.

The biggest difference between the two is the Coens’ decision to hew closely to the source material, Charles Portis’ novel. The novel is told through Mattie’s eyes as an adult narrator, which gives her an increased role and the film a rather different tone. The Coens also preserved a lot of the novel’s dialogue, leading to plenty of laugh-out-loud moments as deadpan remarks (“You are not La Boeuf,” Rooster observes as a bearskin-clad stranger approaches) and puffed-up prose. Lastly, not having to worry about filling The Duke’s shoes allows The Dude to interpret Rooster Cogburn in his own fashion. The result is a buffoonish, broken-down drunk who can nevertheless get the job done with amazing efficiency when the stakes are raised.

Bridges’ co-stars are every bit as good. Damon’s easily offended La Boeuf has comic relief trappings, but he’s still credible as a man of action. Ditto Brolin’s Chaney, a poorly regarded lout who is nevertheless a menace. Curiously, the role of gang leader Ned Pepper (Duvall in the original version) is played by Barry Pepper, who makes the most of his brief screen time.

However, the film is truly buoyed by Steinfeld, a relative newcomer who more than holds her own. She approaches Mattie with poise and makes the character almost admirable without betraying the book’s vision. The cinematic Mattie is still headstrong, insistent, and brave beyond her years, but not quite as insufferable as the literary narrator.

The look and sound of the film are top-notch thanks to the return of frequent Coen collaborators Roger Deakins (cinematography) and Carter Burwell (music). There is a good amount of frontier violence here, but True Grit has nothing on the Coens’ last foray out west (No Country For Old Men).

Whether it’s dark comedy or stark drama, an homage-laden original or a faithful adaptation, the Coen Brothers have proven in recent years that they are capable of writing and directing just about any kind of film. Where True Grit ranks among their other films is a matter of fan opinion (the competition is stiff, to say the least), but it singlehandedly defies the notion that remakes of decent flicks will be inherently inferior.

8.25/10

Sunday, December 26, 2010

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

Tron: Legacy

In 1989, revolutionary software engineer Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges) abruptly disappeared. Twenty years later, his son Sam (Garrett Hedlund) is a hacktivist loner struggling to make sense of his father’s disappearance. A mysterious page leads Sam back to Kevin’s arcade, where he is sucked into The Grid, the digital world of his father’s creation. On the run from the tyrannical A.I. Clu (Bridges again, digitally de-aged), Sam must reunite with Kevin and return to the real world before the programs do.

When the original Tron was released in 1982, it generated a cult following and critical praise in spite of its confusing plot due to impressive special effects and an inventive premise. This much-belated sequel increases both the visual splendor and the disorienting plotting, to a mixed, though largely favorable result.

Those who enjoyed the original Tron will be pleased to see Bridges and Bruce Boxleitner (as fellow programmer Alan Bradley and his A.I. counterpart, Tron) back in action. However, aside from those two, series creator Steven Lisberger serving as a producer, and Cillian Murphy cameoing as the original antagonist’s son, there isn’t enough continuity here to overwhelm a first-time viewer. This is a definite plus, in that the film is confusing enough as-is. The double-dose of Jeff Bridges is visually jarring, and Clu’s turn to the dark side is extremely abrupt: basically, he turns on his creator when Kevin forsakes him for Isomorphic Algorithms, advanced creations that could potentially unlock tons of human mysteries. How exactly this would happen is anyone’s guess.

Visually, the film captures the look and feel of being inside a 1980s computer game. So strong is the disconnect between that world and ours that it is extremely difficult to accurately describe – picture a lot of black space with brightly colored lines everywhere. That the film can present this world as being awe-inspiring rather than ridiculous is a strong indication of how much money and effort went into the design.

Unfortunately, the film is ridiculous in other ways. This being a Disney production, the acting is prone to cheesiness. Bridges as Clu ventures into cardboard-cutout villainy while Bridges as Flynn channels an aged version of The Dude. Michael Sheen is also excessively campy a David Bowie-esque digital nightclub owner. On the flip side, Hedlund is credible in the lead, Olivia Wilde is passable, and Daft Punk amusingly cameo as DJs in Sheen’s nightclub.

Tron: Legacy is perhaps too conventional in its approach to generate the same kind of analysis that came in the wake of The Matrix films. It is also too complex and convoluted to function as pure entertainment. But as mildly thought-provoking eye candy featuring Jeff Bridges doing Jeff Bridges things, it reaches a solid middle ground.

7.75/10

When the original Tron was released in 1982, it generated a cult following and critical praise in spite of its confusing plot due to impressive special effects and an inventive premise. This much-belated sequel increases both the visual splendor and the disorienting plotting, to a mixed, though largely favorable result.

Those who enjoyed the original Tron will be pleased to see Bridges and Bruce Boxleitner (as fellow programmer Alan Bradley and his A.I. counterpart, Tron) back in action. However, aside from those two, series creator Steven Lisberger serving as a producer, and Cillian Murphy cameoing as the original antagonist’s son, there isn’t enough continuity here to overwhelm a first-time viewer. This is a definite plus, in that the film is confusing enough as-is. The double-dose of Jeff Bridges is visually jarring, and Clu’s turn to the dark side is extremely abrupt: basically, he turns on his creator when Kevin forsakes him for Isomorphic Algorithms, advanced creations that could potentially unlock tons of human mysteries. How exactly this would happen is anyone’s guess.

Visually, the film captures the look and feel of being inside a 1980s computer game. So strong is the disconnect between that world and ours that it is extremely difficult to accurately describe – picture a lot of black space with brightly colored lines everywhere. That the film can present this world as being awe-inspiring rather than ridiculous is a strong indication of how much money and effort went into the design.

Unfortunately, the film is ridiculous in other ways. This being a Disney production, the acting is prone to cheesiness. Bridges as Clu ventures into cardboard-cutout villainy while Bridges as Flynn channels an aged version of The Dude. Michael Sheen is also excessively campy a David Bowie-esque digital nightclub owner. On the flip side, Hedlund is credible in the lead, Olivia Wilde is passable, and Daft Punk amusingly cameo as DJs in Sheen’s nightclub.

Tron: Legacy is perhaps too conventional in its approach to generate the same kind of analysis that came in the wake of The Matrix films. It is also too complex and convoluted to function as pure entertainment. But as mildly thought-provoking eye candy featuring Jeff Bridges doing Jeff Bridges things, it reaches a solid middle ground.

7.75/10

Dominion

In this Medieval-themed card game, two to four players compete to amass the most property in the kingdom. From an initial deal of five coin and three property cards, players build their decks by amassing action cards as well as additional coin and property, each with a different value. Action cards may do anything from grant the player more coin to penalize an opponent. When an end condition is reached (typically, all the highest-value property cards have been drawn), the property is totaled and a winner is declared.

The appeal of Dominion lies in its flexibility. There are more than a dozen different action cards, and they can be mixed and matched to build a custom game every time. Through trial and error, it is easy to eliminate any cards you don’t like (I’m looking at you, Adventurer) and focus on those that make the game the most interesting.

In addition, Dominion forces players to think strategically. If your opponents are buying Thief (costs you coin) and Witch (costs you property value via “curse” cards) cards, you’d better stock up on Moats (defends against attack cards). If property is disappearing fast, you’d be wise to grab what you can, even if it’s a paltry Estate. Not only does this forced adaptability increase player involvement in the game, but it deemphasizes luck. You don’t like the hand you drew? Guess what, you bought the cards.

Like all games, there is a bit of a learning curve. Dominion’s multi-phase (one action and one buy) turns take some getting used to, and the relative lack of warfare (Militia cards aside) may make the game seem boring to newcomers. Once you adjust, however, it becomes both easy and engrossing. Each configuration of cards and group of opponents bring new challenges. There are also expansion packs to increase the possibilities.

8/10

The appeal of Dominion lies in its flexibility. There are more than a dozen different action cards, and they can be mixed and matched to build a custom game every time. Through trial and error, it is easy to eliminate any cards you don’t like (I’m looking at you, Adventurer) and focus on those that make the game the most interesting.

In addition, Dominion forces players to think strategically. If your opponents are buying Thief (costs you coin) and Witch (costs you property value via “curse” cards) cards, you’d better stock up on Moats (defends against attack cards). If property is disappearing fast, you’d be wise to grab what you can, even if it’s a paltry Estate. Not only does this forced adaptability increase player involvement in the game, but it deemphasizes luck. You don’t like the hand you drew? Guess what, you bought the cards.

Like all games, there is a bit of a learning curve. Dominion’s multi-phase (one action and one buy) turns take some getting used to, and the relative lack of warfare (Militia cards aside) may make the game seem boring to newcomers. Once you adjust, however, it becomes both easy and engrossing. Each configuration of cards and group of opponents bring new challenges. There are also expansion packs to increase the possibilities.

8/10

Sunday, December 19, 2010

Over the Edge

Trapped in a dull planned community, misunderstood youth seek refuge in audacity. Their drug-dealing and petty crime goes unnoticed at first, but increasing tension with local police eventually leads to tragedy and violent reprisals.

Released in 1979, it’s hard to tell if Jonathan Kaplan’s film was intended as edgy social criticism or as a B-grade message movie. It’s dated, to say the least – teenagers engaging in debauchery is hardly shocking these days – but there’s still an unsettling core here. The idea that teenagers should be regarded as people with legitimate issues and concerns and not as a municipal image problem is a lesson the largely clueless adults learn all too late.

Unfortunately, the film’s thematic promise is nearly betrayed by acting that is mediocre at best. Matt Dillon makes his debut as a gun-toting delinquent, but no one will confuse him for James Dean. The chief protagonist, Carl (Michael Eric Kramer), is supposed to be torn between his parents and his friends, but the conflict is heavily skewed to favor the latter. Starpower may be overrated, but Over the Edge could have used some stronger acting, even if only in a glorified cameo.

On the flip side, the movie does boast a quality soundtrack (Van Halen, The Ramones, and Cheap Trick, among other bands) and the cinematography effectively captures the suffocating yuppie boredom of New Granada.

The best reasons for watching this movie, however, come from real life. It was inspired by a San Francisco article about a youth crime spree and it went on to have a profound effect on one viewer, Kurt Cobain. Watch the video for “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and bask in the similarities.

7.25/10

Released in 1979, it’s hard to tell if Jonathan Kaplan’s film was intended as edgy social criticism or as a B-grade message movie. It’s dated, to say the least – teenagers engaging in debauchery is hardly shocking these days – but there’s still an unsettling core here. The idea that teenagers should be regarded as people with legitimate issues and concerns and not as a municipal image problem is a lesson the largely clueless adults learn all too late.

Unfortunately, the film’s thematic promise is nearly betrayed by acting that is mediocre at best. Matt Dillon makes his debut as a gun-toting delinquent, but no one will confuse him for James Dean. The chief protagonist, Carl (Michael Eric Kramer), is supposed to be torn between his parents and his friends, but the conflict is heavily skewed to favor the latter. Starpower may be overrated, but Over the Edge could have used some stronger acting, even if only in a glorified cameo.

On the flip side, the movie does boast a quality soundtrack (Van Halen, The Ramones, and Cheap Trick, among other bands) and the cinematography effectively captures the suffocating yuppie boredom of New Granada.

The best reasons for watching this movie, however, come from real life. It was inspired by a San Francisco article about a youth crime spree and it went on to have a profound effect on one viewer, Kurt Cobain. Watch the video for “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and bask in the similarities.

7.25/10

Firefly

500 years in the future amid a galaxy full of colonized planets, former resistance fighter Mal Reynolds (Nathan Fillion) captains the Serenity, a cargo ship for hire. The ragtag crew includes tough second-in-command Zoe (Gina Torres), her laidback pilot husband Wash (Alan Tudyk), perpetually cheerful engineer Kaylee (Jewel Staite), sophisticated courtesan Inara (Morena Baccarin), and uncouth muscle-for-hire Jayne (Adam Baldwin). The crew is soon joined by a pair of fugitives on the run from the ruling Alliance: upper-class doctor Simon Tam (Sean Maher) and his disturbed teenage sister, River (Summer Glau). As the Serenity crew loots and smuggles its way across the galaxy, it must stay one step ahead of crime bosses, cannibals, and, of course, the Alliance.

The epitome of a cult classic, Firefly aired for a single season in 2002. When Fox pulled the plug, fan outrage was such that it inspired series creator Joss Whedon to put together a movie (2005’s Serenity) just to tie up some loose ends. To say that the franchise deserved a longer lifespan is like saying that the Titanic should have had more than one voyage.

To put it simply, Firefly offers something for everyone. Fans of Whedon’s previous series (Buffy the Vampire Slayer) can rejoice at his trademark snarky dialogue, while those who found Buffy incredibly silly can revel in Firefly’s frontier grit. A fast-paced space western with obvious Star Wars influences (as a risk-taking anti-hero, Mal frequently channels Han Solo), the show still avoids many genre clichés. Alliance soldiers, for example, are less the minions of Big Brother and more the annoying bureaucratic types who can nevertheless be reasoned with. Likewise, instead of ripping off John Williams, the show opts for a blues number by Sonny Rhodes as its theme song.

This unique vision would amount to naught if the execution wasn’t there. Fortunately, it is – in a big way. Cast to perfection, Firefly presents a crew of misfits who are thoroughly entertaining and engaging if a bit predictable. It’s never a surprise when Mal picks a fight, Jayne contemplates betrayal, or River has a breakdown, but there are more than a few swerves as well. A strong sense of continuity ensures that the stupid decisions of one episode will come back to bite the crew later on as the series progresses.

If there’s one drawback to Firefly, it’s that the short production run leaves a lot of questions unanswered. What exactly is wrong with River Tam doesn’t become fully apparent until the movie, and the mysterious past of “Shepherd” Book isn’t revealed on screen at all.

Eight years after going off the air, Firefly continues to maintain a strong following. That a show which only existed for 14 episodes (not all of which originally aired) can still leave people wanting more nearly a decade later is a testament to its all-around excellence.

8.75/10

The epitome of a cult classic, Firefly aired for a single season in 2002. When Fox pulled the plug, fan outrage was such that it inspired series creator Joss Whedon to put together a movie (2005’s Serenity) just to tie up some loose ends. To say that the franchise deserved a longer lifespan is like saying that the Titanic should have had more than one voyage.

To put it simply, Firefly offers something for everyone. Fans of Whedon’s previous series (Buffy the Vampire Slayer) can rejoice at his trademark snarky dialogue, while those who found Buffy incredibly silly can revel in Firefly’s frontier grit. A fast-paced space western with obvious Star Wars influences (as a risk-taking anti-hero, Mal frequently channels Han Solo), the show still avoids many genre clichés. Alliance soldiers, for example, are less the minions of Big Brother and more the annoying bureaucratic types who can nevertheless be reasoned with. Likewise, instead of ripping off John Williams, the show opts for a blues number by Sonny Rhodes as its theme song.

This unique vision would amount to naught if the execution wasn’t there. Fortunately, it is – in a big way. Cast to perfection, Firefly presents a crew of misfits who are thoroughly entertaining and engaging if a bit predictable. It’s never a surprise when Mal picks a fight, Jayne contemplates betrayal, or River has a breakdown, but there are more than a few swerves as well. A strong sense of continuity ensures that the stupid decisions of one episode will come back to bite the crew later on as the series progresses.

If there’s one drawback to Firefly, it’s that the short production run leaves a lot of questions unanswered. What exactly is wrong with River Tam doesn’t become fully apparent until the movie, and the mysterious past of “Shepherd” Book isn’t revealed on screen at all.

Eight years after going off the air, Firefly continues to maintain a strong following. That a show which only existed for 14 episodes (not all of which originally aired) can still leave people wanting more nearly a decade later is a testament to its all-around excellence.

8.75/10

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

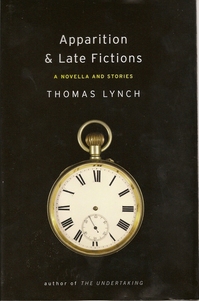

Apparition and Late Fictions

The debut story collection from undertaker-turned-poet Thomas Lynch, Apparition and Late Fictions contains the title novella and four shorter works, all of which are united by a sense of loss.

Plowing through Lynch’s writing is the equivalent of driving a Honda with a 500-horsepower engine. His prose is simply masterful. Whether describing the violence of murder as “hunter-gatherly” or using a pilot’s crisp epaulettes to show a character’s preference for refinement, Lynch’s command of language is as fresh and innovative as it is precise.

Unfortunately, a good turn of phrase does not a good story make. Though an established memoirist and poet, it’s fairly clear that Lynch has yet to fully grow into the role of storyteller. The fiction contained here is ponderously paced and weighed down by an overemphasis on backstory. Worse still, his endings are either abrupt (“Martin never heard from her again.”), asynchronous, or quixotic.

However, this isn’t to say that the collection is pretty prose and nothing more. As a mortician, Lynch excels at creating a pervasive sense of sorrow, whether it be an embalmer grieving for a murder victim (“Bloodsport”), a fisherman mourning his father “Catch and Release”), or a retiree torn up over his several failed marriages (“Hunter’s Moon”). In addition, Lynch succeeds at taking unsympathetic characters and making them pitiable and interesting. The protagonist of “Matinee de Septembre” is a spoiled, elitist academic who ends up hopelessly pining for a Jamaican serving girl half her age while the title novella’s straightlaced preacher-turned-motivational speaker only feels divine inspiration after divorcing his unfaithful wife and engaging in random debauchery. Funny moments are few and far between, but when they work – i.e. a woman demanding a priest annoint a dog because it is a “Catholic” dog – they really work well.

Apparition and Late Fictions is a flawed but promising first effort, worthwhile as an introduction to an author who is likely to impress once he becomes more familiar with his craft.

7.5/10

Plowing through Lynch’s writing is the equivalent of driving a Honda with a 500-horsepower engine. His prose is simply masterful. Whether describing the violence of murder as “hunter-gatherly” or using a pilot’s crisp epaulettes to show a character’s preference for refinement, Lynch’s command of language is as fresh and innovative as it is precise.

Unfortunately, a good turn of phrase does not a good story make. Though an established memoirist and poet, it’s fairly clear that Lynch has yet to fully grow into the role of storyteller. The fiction contained here is ponderously paced and weighed down by an overemphasis on backstory. Worse still, his endings are either abrupt (“Martin never heard from her again.”), asynchronous, or quixotic.

However, this isn’t to say that the collection is pretty prose and nothing more. As a mortician, Lynch excels at creating a pervasive sense of sorrow, whether it be an embalmer grieving for a murder victim (“Bloodsport”), a fisherman mourning his father “Catch and Release”), or a retiree torn up over his several failed marriages (“Hunter’s Moon”). In addition, Lynch succeeds at taking unsympathetic characters and making them pitiable and interesting. The protagonist of “Matinee de Septembre” is a spoiled, elitist academic who ends up hopelessly pining for a Jamaican serving girl half her age while the title novella’s straightlaced preacher-turned-motivational speaker only feels divine inspiration after divorcing his unfaithful wife and engaging in random debauchery. Funny moments are few and far between, but when they work – i.e. a woman demanding a priest annoint a dog because it is a “Catholic” dog – they really work well.

Apparition and Late Fictions is a flawed but promising first effort, worthwhile as an introduction to an author who is likely to impress once he becomes more familiar with his craft.

7.5/10

Monday, November 15, 2010

Red

Struggling to adjust to civilian life, retired CIA hitman Frank Moses (Bruce Willis) tries to woo Sarah (Mary-Louise Parker), a customer service rep several hundred miles away. Unfortunately, before he can make his move, someone at Langley decides he’s a liability and tries to eliminate him and his former (and equally over-the-hill) teammates. Naturally, they decide to fight back.

Directed by Robert Schwentke and adapted from a limited-series DC comic book of the same name, Red offers perhaps the best balance of action and comedy since Hot Fuzz. The sensibility is flat-out ridiculous (case-in-point: the CIA’s secret files are guarded by a somehow-not-dead Ernest Borgnine), but there enough explosions and well-rounded characters to keep things interesting.

Led by a seemingly ageless (ironic, given the premise) Willis, the cast is mostly game. Bald Bruce can still run, shoot, and fight with the poise of a late-80s John McLane. He’s flanked by a hapless, sympathetic Parker, an affably deadly Russian (Brian Cox, pulling off yet another accent), and a demure Englishwoman (Helen Mirren), who happens to be a lethal sniper. John Malkovich nearly steals the show, however, as a paranoid, gun-crazy, bunker-dwelling loon – a comic counterpart to his character from In the Line of Fire. Morgan Freeman is in the mix too as Frank’s mentor, but his screen time is all-too-brief.

Unfortunately, the bad guys and secondary characters aren’t nearly as well-cast or earnestly portrayed. Karl Urban is a bit too likeable as Willis’ would-be replacement at the Agency, Julian McMahon looks like neither a vice president nor a former soldier (he’s supposed to be both), and a tough-to-recognize Richard Dreyfuss hams it up as a smarmy, politically connected arms dealer. These shortcomings rob the film of its needed tension and steer it toward a very predictable conclusion.

Neither innovative nor plausible, Red nevertheless hits home as an enjoyable action-comedy that offers unexpected insight on the perils of both ageism and growing old.

7.5

Directed by Robert Schwentke and adapted from a limited-series DC comic book of the same name, Red offers perhaps the best balance of action and comedy since Hot Fuzz. The sensibility is flat-out ridiculous (case-in-point: the CIA’s secret files are guarded by a somehow-not-dead Ernest Borgnine), but there enough explosions and well-rounded characters to keep things interesting.

Led by a seemingly ageless (ironic, given the premise) Willis, the cast is mostly game. Bald Bruce can still run, shoot, and fight with the poise of a late-80s John McLane. He’s flanked by a hapless, sympathetic Parker, an affably deadly Russian (Brian Cox, pulling off yet another accent), and a demure Englishwoman (Helen Mirren), who happens to be a lethal sniper. John Malkovich nearly steals the show, however, as a paranoid, gun-crazy, bunker-dwelling loon – a comic counterpart to his character from In the Line of Fire. Morgan Freeman is in the mix too as Frank’s mentor, but his screen time is all-too-brief.

Unfortunately, the bad guys and secondary characters aren’t nearly as well-cast or earnestly portrayed. Karl Urban is a bit too likeable as Willis’ would-be replacement at the Agency, Julian McMahon looks like neither a vice president nor a former soldier (he’s supposed to be both), and a tough-to-recognize Richard Dreyfuss hams it up as a smarmy, politically connected arms dealer. These shortcomings rob the film of its needed tension and steer it toward a very predictable conclusion.

Neither innovative nor plausible, Red nevertheless hits home as an enjoyable action-comedy that offers unexpected insight on the perils of both ageism and growing old.

7.5

Monday, October 11, 2010

Fincastles Diner (CLOSED)

NOTE: Fincastles has since closed. Mid City Sandwich Company opened in its location but has also since closed as well. White and Wood, a wine bar, is the current tenant.

Located at 218 South Elm Street in downtown Greensboro, Fincastles offers burgers, hot dogs, sandwiches, and other lighter fare. Limited outdoor seating is available.

Fincastles may have an Irish-sounding name, but don’t come here looking for corned beef and cabbage– the cuisine is pure American Southern. Regional flourishes include sides like fried green tomatoes and crawfish tails, as well as Carolina-style (chili, mustard, onions, and slaw) burgers and dogs.

Unfortunately, this is one case where distinction and variety are poor stand-ins for quality. An Elm Street burger (pickles and cheese) was misshapen and surprisingly small, while the pimento cheese sauce – they are big on that here – is an acquired taste, to say the least. The best thing about it was the sourdough bun. Sweet potato fries fared better, but the portion size was hardly generous.

The interior of Fincastles is decidedly retro. From the gaudy tile and the old-school jukebox to the plus-sized Coke bottle decoration and the long service counter, the place screams vintage small-town burger joint, even though it’s in the heart of a major city. Needless to say, this is not a good place to enjoy a quiet meal…or a prompt one. The lone server was friendly enough, but no match for the sizeable lunch crowd.

Given the small servings and the boisterous ambience, one would at least expect Fincastles to be a bargain. No dice. Burgers run $4 and up, with no sides. Add a side and a drink to round out the meal, and you’re looking at paying double-digits for something you can get better and cheaper at a fast food establishment.

The location and the menu’s innovations make Fincastle’s worth an occasional visit, but there is no shortage of superior lunch options.

6.75/10

Labels:

Burgers and Sandwiches,

Greensboro,

NC,

restaurant review

Saturday, October 9, 2010

The Social Network

Dumped by his girlfriend and eager to impress a prestigious club, Harvard computer geek Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) creates a Web site that allows students to rate their female classmates. After much controversy and consternation, Zuckerberg and his friends create Facebook. As the social networking site takes off and launches Zuckerberg to newfound fame and fortune, he falls into conflict with his best friend/cofounder (Andrew Garfield) and a pair of privileged twins (Armie Hammer) whose idea he might have stolen.

I was in college when Facebook was launched, and I remember how quickly and voraciously it spread, converting naysayers and adding new schools and new members at an unfathomable pace. Naturally, the story behind this phenomenon is of curiosity to many members of my generation, whether they love or loathe Zuckerberg’s creation. But what makes The Social Network so interesting is that the story behind the story is almost as compelling and curious as the film itself.

Directed by David Fincher and written by Aaron Sorkin (a wonderfully paranoid downer and a clever leftist technophobe, respectively), The Social Network bares only a casual resemblance to the truth. Eisenberg plays Zuckerberg as an isolated, insecure, yet intelligent jerk. Obviously, the young billionaire didn’t get to where he is by being Mr. Sunshine, but the fact that he was in a stable relationship while the film was being made clashes inconveniently with the celluloid image. Likewise, co-founder Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield) is made to be a much more sympathetic character while downplaying his incompetence as CFO, and Saverin’s rival, Napster founder Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake), is given a more antagonistic role – no wonder given that Saverin served as a consultant for the book that served as the movie’s source material.

Despite the overt factual manipulation, The Social Network remains a generally well-crafted film. The leads deliver memorable performances, Sorkin’s dialogue is as sharp as ever, and the Trent Reznor/Atticus Ross soundtrack hits all the right notes. Fincher caught some flak for his reliance on CGI – how else could he get both Winklevoss brothers in the same shot? – but the end result is fairly seamless.

Like Oliver Stone’s W., The Social Network suffers from not achieving enough chronological distance from its subject. Both films also subvert reality in the name of storytelling. The key difference is that the Fincher/Sorkin effort is marked by a more consistent tone and a more harmonious creative vision.

8/10

I was in college when Facebook was launched, and I remember how quickly and voraciously it spread, converting naysayers and adding new schools and new members at an unfathomable pace. Naturally, the story behind this phenomenon is of curiosity to many members of my generation, whether they love or loathe Zuckerberg’s creation. But what makes The Social Network so interesting is that the story behind the story is almost as compelling and curious as the film itself.

Directed by David Fincher and written by Aaron Sorkin (a wonderfully paranoid downer and a clever leftist technophobe, respectively), The Social Network bares only a casual resemblance to the truth. Eisenberg plays Zuckerberg as an isolated, insecure, yet intelligent jerk. Obviously, the young billionaire didn’t get to where he is by being Mr. Sunshine, but the fact that he was in a stable relationship while the film was being made clashes inconveniently with the celluloid image. Likewise, co-founder Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield) is made to be a much more sympathetic character while downplaying his incompetence as CFO, and Saverin’s rival, Napster founder Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake), is given a more antagonistic role – no wonder given that Saverin served as a consultant for the book that served as the movie’s source material.

Despite the overt factual manipulation, The Social Network remains a generally well-crafted film. The leads deliver memorable performances, Sorkin’s dialogue is as sharp as ever, and the Trent Reznor/Atticus Ross soundtrack hits all the right notes. Fincher caught some flak for his reliance on CGI – how else could he get both Winklevoss brothers in the same shot? – but the end result is fairly seamless.

Like Oliver Stone’s W., The Social Network suffers from not achieving enough chronological distance from its subject. Both films also subvert reality in the name of storytelling. The key difference is that the Fincher/Sorkin effort is marked by a more consistent tone and a more harmonious creative vision.

8/10

Kiosco Mexican Grill

Located at 3011 Spring Garden Street, Kiosco offers tacos, burritos, fajitas, and a wide variety of Mexican house specials. There is a full-service bar, and outdoor seating is available. Food and drink specials change daily.

Mexican dining in Greensboro is largely a series of trade-offs. Some establishments can make a mean taco (El Azteca), but lack ambience while others offer plenty of seating and variety (El Mariachi), but don’t always guarantee a good meal. Of all the local Mexican restaurants I’ve been to (six at last count), Kiosco comes the closest to offering the total package.

First, the food: the menu isn’t quite as stacked at El Mariachi’s, but it’s still plenty expansive in its own right. There are scores of specials for the lunch crowd, but those coming for dinner will still find plenty, from classic carnitas to sizzling steak fajitas and a few things you can’t find elsewhere. Ever want the contents of a burrito Texano tossed together, minus the burrito, and topped with cheese? They have that here, and they do it well: the A.C.P. Texano is well-seasoned and not too dry. Full-sized and half-sized options ensure the right fit for every appetite.

The food would be a draw in and of itself, but the service at Kiosco is spectacular. Servers are friendly, abundant, and lightning-quick. You won’t be sitting for more than a minute before someone takes your drink order, and that glass won’t remain empty for long unless you want it to be. Both the chips (complimentary with salsa, as they should be) and the check were delivered promptly and amicably.

Kiosco isn’t a large place, but the seating capacity is deceptive. Though the booths are few, the long table and the bar seat many. Outdoor seating in nicer weather further increases the capacity. Kiosco’s interior is as dark, calm and tastefully subdued as Mexico Restaurant’s is garishly colorful. A few TVs add appeal for sports fans.

One would expect to overpay for all these intangibles, but Kiosco manages to keep it reasonable. If you stick with the half-size on an entrée (adequate for a non-famished party of one), you can feed yourself for under $10. Nothing here is a steal, but the quality justifies the price.

Cheaper and gaudier/more fun Mexican restaurants exist, but Kiosco offers the best blend of food, service, and value. Until another establishment decides to step up its game, Kiosco gets my vote for Greensboro’s finest.

8.5/10

Mexican dining in Greensboro is largely a series of trade-offs. Some establishments can make a mean taco (El Azteca), but lack ambience while others offer plenty of seating and variety (El Mariachi), but don’t always guarantee a good meal. Of all the local Mexican restaurants I’ve been to (six at last count), Kiosco comes the closest to offering the total package.

First, the food: the menu isn’t quite as stacked at El Mariachi’s, but it’s still plenty expansive in its own right. There are scores of specials for the lunch crowd, but those coming for dinner will still find plenty, from classic carnitas to sizzling steak fajitas and a few things you can’t find elsewhere. Ever want the contents of a burrito Texano tossed together, minus the burrito, and topped with cheese? They have that here, and they do it well: the A.C.P. Texano is well-seasoned and not too dry. Full-sized and half-sized options ensure the right fit for every appetite.

The food would be a draw in and of itself, but the service at Kiosco is spectacular. Servers are friendly, abundant, and lightning-quick. You won’t be sitting for more than a minute before someone takes your drink order, and that glass won’t remain empty for long unless you want it to be. Both the chips (complimentary with salsa, as they should be) and the check were delivered promptly and amicably.

Kiosco isn’t a large place, but the seating capacity is deceptive. Though the booths are few, the long table and the bar seat many. Outdoor seating in nicer weather further increases the capacity. Kiosco’s interior is as dark, calm and tastefully subdued as Mexico Restaurant’s is garishly colorful. A few TVs add appeal for sports fans.

One would expect to overpay for all these intangibles, but Kiosco manages to keep it reasonable. If you stick with the half-size on an entrée (adequate for a non-famished party of one), you can feed yourself for under $10. Nothing here is a steal, but the quality justifies the price.

Cheaper and gaudier/more fun Mexican restaurants exist, but Kiosco offers the best blend of food, service, and value. Until another establishment decides to step up its game, Kiosco gets my vote for Greensboro’s finest.

8.5/10

Twilight

Guest Review by Jen Julian

The book’s seventeen-year-old protagonist, Bella Swan, is probably the best example of Meyer’s manipulative handiwork. Bella, the product of divorced parents, moves to Forks, Washington to live with her dad and meets dreamy, brooding vamp Edward Cullen at her local high school (that’s the basic plot, for those of you who’ve been living under a rock). A different protagonist could have made Twilight into a bearable or even meaningful young adult book. But Bella is not so much a character as she is an expertly designed placeholder for the reader. She fluctuates wildly from self-pity, to disdain, to blind rapture for the godly, often condescending Edward. Basically everything that she feels is unreasonable, though still somehow believable, given that she is exactly how a self-centered teenager would portray herself if inserted into a novel like this one. Bella is just nice enough that she doesn’t have to face confrontation, she never reciprocates to the high school peers that extend themselves to her, and on a whim she performs acts of unnecessary selflessness, the author’s way of reminding us that she is an innocent, sacrificial lamb. Never once does Meyer ask us to question this character’s behavior, and by the end of the novel, Bella has received everything she could possibly want with little effort. The appeal to teenage readers should be obvious.

Edward is also an overt manipulation, a beautiful, self-tormenting “vegetarian” vampire that abstains, both from sex and human blood. He does sparkle in the sun, literally, but this deviation from traditional vampire lore serves no purpose for the “plot” and is the least of Twilight’s problems. Edward is madly in love with Bella but also holds a burning desire to eat her. He stalks her, sneaks into her room to watch her sleep, and consistently overpowers her both physically and emotionally. While the subtext is disconcerting, Meyer’s preferred message is clear: Edward is there as a protector. He is to protect Bella from everything, including her own rampant desires and the dangers that their relationship imposes. Young women just entering into the scary world of adulthood might find this kind of controlled relationship comforting. Combine that with Bella Swan’s inescapable relatability and you’ve got a legion of hypnotized fans.

Twilight is most enjoyed by teen girls and by adult women who have fond memories of their first high school crushes. It is particularly enjoyed by those who would prefer to remain as teenagers forever, as this is the kind of reward that Meyer’s novel offers. Edward is gorgeous, rich, powerful and immortal, and the adult world beyond him is portrayed as dull and insufficient. Most all characters, Bella’s high school friends, parents and teachers, are insignificant when up against Edward and his vampire family. Twilight, on a whole, is the kind of novel that persuades women to remain locked up inside their heads, discouraging them from exploring the world of responsibility and adulthood. Meyer, something like the literary equivalent of Dr. Frankenstein, has tapped into an overflowing subconscious vein, and she has brought the hulking monster to life.

1.5/10 for the writing, 6/10 for the evil ingenuity

Sunday, September 26, 2010

The Town

Doug MacRay (Ben Affleck), a former hockey prospect-turned-thief from the rough Boston neighborhood of Charlestown, robs banks with best friend Jem (Jeremy Renner) and their crew. After briefly being taken hostage by the gang, bank manager Claire Keesey (Rebecca Hall) becomes traumatized and falls into the arms of Doug, unaware that he was one of her abductors. Meanwhile, ruthless FBI agent Adam Frawley (Jon Hamm) is determined to take down the crew and their boss, Fergus the Florist (Peter Postlethwaite).

In a strange bit of irony, the nicer and more gentrified Boston seems to get, the grittier its cinema becomes. The past decade has given us Mystic River, Gone, Baby, Gone, and The Departed. The Town is certainly in the same vein (with a healthy smattering of Heat thrown in for good measure), though not quite up to the level of its cinematic forbearers.

Both the film’s strengths and shortcomings lie with Affleck, who also directed and co-wrote the script (adapting Chuck Hogan’s novel Prince of Thieves). The film has a tough urban sensibility to it, and the action sequences are competent, if not exactly groundbreaking (The Dark Knight may have raised the bar for bank robbery scenes to an impossibly high level). Praise should be given, however, for somehow cobbling together a credible chase involving narrow streets and a minivan.

Performances were likewise convincing, to the point that Boston accents occasionally became indecipherably thick. Affleck, Hamm, Hall, and especially Renner (a hotheaded thug with a strong sense of loyalty) do a good job of imbuing their characters with depth and moral ambiguity, but this is one case where “conflicted” doesn’t equal “interesting.” Are we really supposed to be surprised that professional criminals still have humanity or that the FBI would resort to underhanded tactics?

Sadly, this lack of profundity permeates the film’s overly conventional plotting. Not only is the ending clichéd and predictable, but you can probably make good money betting on the victims and survivors. Unlike an Eastwood or a Scorcese film or even Affleck’s own previous effort, shocking moments are as scarce here as a Yankees fan in Fenway.

Engrossing, stark, and generally well-crafted, The Town is a serviceable crime drama which disappoints only in its inability to transcend the boundaries and expectations of its genre.

7.25/10

In a strange bit of irony, the nicer and more gentrified Boston seems to get, the grittier its cinema becomes. The past decade has given us Mystic River, Gone, Baby, Gone, and The Departed. The Town is certainly in the same vein (with a healthy smattering of Heat thrown in for good measure), though not quite up to the level of its cinematic forbearers.

Both the film’s strengths and shortcomings lie with Affleck, who also directed and co-wrote the script (adapting Chuck Hogan’s novel Prince of Thieves). The film has a tough urban sensibility to it, and the action sequences are competent, if not exactly groundbreaking (The Dark Knight may have raised the bar for bank robbery scenes to an impossibly high level). Praise should be given, however, for somehow cobbling together a credible chase involving narrow streets and a minivan.

Performances were likewise convincing, to the point that Boston accents occasionally became indecipherably thick. Affleck, Hamm, Hall, and especially Renner (a hotheaded thug with a strong sense of loyalty) do a good job of imbuing their characters with depth and moral ambiguity, but this is one case where “conflicted” doesn’t equal “interesting.” Are we really supposed to be surprised that professional criminals still have humanity or that the FBI would resort to underhanded tactics?

Sadly, this lack of profundity permeates the film’s overly conventional plotting. Not only is the ending clichéd and predictable, but you can probably make good money betting on the victims and survivors. Unlike an Eastwood or a Scorcese film or even Affleck’s own previous effort, shocking moments are as scarce here as a Yankees fan in Fenway.

Engrossing, stark, and generally well-crafted, The Town is a serviceable crime drama which disappoints only in its inability to transcend the boundaries and expectations of its genre.

7.25/10

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Bonsai Japanese Restaurant & Sushi Bar (CLOSED)

NOTE: Bonsai has since closed.

Located beside the Hobby Lobby at 1315 Bridford Parkway, Bonsai offers a wide variety of sushi and Japanese entrees. Alcohol is available, the menu includes vegetarian options, and specials change daily.

Hibachi grills are typically a polarizing issue. Some love the theatricality of food being dramatically chopped and tossed on a hot grill; others balk at the communal seating. Bonsai deftly sidesteps the debate by offering hibachi-style entrees minus the fanfare. You can take your pick of chicken, steak, pork, seafood, or some combination thereof, served with rice and your choice of vegetable. The presentation leaves something to be desired – it’s all lumped together on a plate – but the food tastes better than you’d find at a mall food court establishment. A hint of blandness is easily corrected thanks to a dollop of ginger, teriyaki, or white sauce.

Spacious and booth-laden, Bonsai’s interior suggests a pricier menu than is actually available. Entrees start at an uber-reasonable $6, and sushi rolls can be had for as low as $4. You can feed yourself easily for under $10, a surprise given the amount and quality of food available.

Service at Bonsai is uneven. Servers are certainly polite, but a bit on the slow side even when there isn’t a crowd. Twice, a waiter brought out more sushi than was ordered, only to quickly realize the mistake.

Bonsai lacks the flair of other Japanese establishments, and you won’t be guaranteed a great dining experience, but the price makes it hard to pass up.

7.5/10

Labels:

Greensboro,

Japanese Restaurants,

NC,

restaurant review

Sunday, August 22, 2010

The Expendables

A group of elite mercenaries led by Barney Ross (Sylvester Stallone) is contracted by a shady CIA operative (Bruce Willis) to take out the ruling general (David Zayas) of a resource-rich island. Despite his misgivings about the mission, Ross falls for the general’s idealistic daughter (Gisele Itie) and decides to make a difference. But will the general’s backer, a former CIA agent-turned- drug profiteer (Eric Roberts) strike first?

Directed by Stallone and featuring plenty of familiar faces (Mickey Rourke, Dolph Lundgren, Jason Statham, Jet Li, Steve Austin, and, in a cameo, Arnold Schwarzenegger), The Expendables is an homage to the violent action movies of the 1980s. It nails many of the genre’s conventions, but that isn’t necessarily a good thing. Like countless interchangeable explosionfests of yesteryear, The Expendables features paper-thin plotting, flat characterization, substandard acting (Rourke being perhaps the lone exception), and a ridiculously high body count.

What saves The Expendables from being a B-movie with an intriguing cast is its postmodern, tongue-in-cheek sensibility. The script is loaded with in-jokes (Willis’ character shares a name with the Senate committee that depowered the CIA, Ah-nold’s character is mocked for wanting to be president, etc.) and several legitimately funny moments. Lundgren’s character is also a fitting metaphor for the action hero as a whole: drug-addled, unstable, and difficult to work with.

In addition, the action sequences are exciting and credible. Stallone is in great shape for someone on the wrong side of 60, Statham and Li demonstrate their martial arts skills (the former also throws a mean knife), and anyone who wanted to see wrestling legend Austin fight MMA legend Randy Couture will have plenty to cheer about.

The Expendables certainly isn’t breaking any new ground and some will consider it a disappointment in the sense that it remains gleefully shallow despite its self-aware underpinnings. But by the standards of its (admittedly limited) genre, it’s a slam-dunk.

7/10

Directed by Stallone and featuring plenty of familiar faces (Mickey Rourke, Dolph Lundgren, Jason Statham, Jet Li, Steve Austin, and, in a cameo, Arnold Schwarzenegger), The Expendables is an homage to the violent action movies of the 1980s. It nails many of the genre’s conventions, but that isn’t necessarily a good thing. Like countless interchangeable explosionfests of yesteryear, The Expendables features paper-thin plotting, flat characterization, substandard acting (Rourke being perhaps the lone exception), and a ridiculously high body count.

What saves The Expendables from being a B-movie with an intriguing cast is its postmodern, tongue-in-cheek sensibility. The script is loaded with in-jokes (Willis’ character shares a name with the Senate committee that depowered the CIA, Ah-nold’s character is mocked for wanting to be president, etc.) and several legitimately funny moments. Lundgren’s character is also a fitting metaphor for the action hero as a whole: drug-addled, unstable, and difficult to work with.

In addition, the action sequences are exciting and credible. Stallone is in great shape for someone on the wrong side of 60, Statham and Li demonstrate their martial arts skills (the former also throws a mean knife), and anyone who wanted to see wrestling legend Austin fight MMA legend Randy Couture will have plenty to cheer about.

The Expendables certainly isn’t breaking any new ground and some will consider it a disappointment in the sense that it remains gleefully shallow despite its self-aware underpinnings. But by the standards of its (admittedly limited) genre, it’s a slam-dunk.

7/10

Sunday, August 8, 2010

Crazy Heart

Bad Blake (Jeff Bridges) is a washed-up, alcoholic country music star who is reduced to opening and writing songs for his former protégé, Tommy Sweet (Colin Farrell). When journalist Jean Craddock (Maggie Gyllenhaal) approaches him for an interview, they connect and he becomes a father figure to his young son. But will Blake, who is already alienated from his biological son, allow his bad habits to screw up the opportunity?

Crazy Heart is ample evidence that a great performance does not a great movie make. Scott Cooper’s film is slow-paced and conventional to the point of tired. There are numerous similarities to Tender Mercies, right on down to a shared cast member (Robert Duvall). And didn’t Mickey Rourke’s turn in The Wrestler make the “aging screwed-up has-been turns his life around” subgenre obsolete?

Nevertheless, this isn’t worth discarding. Bridges, in an Oscar-winning role, is excellent as the irrepressible Blake, a composite of Kris Kristofferson, Merle Haggard, and several lesser-known musicians. Gyllenhaal and Duvall (as Blake’s sympathetic friend) are rock-solid as voices of reason. Even Farrell is strangely credible as the young upstart Sweet.

Fans of country music will probably be enthralled by the behind-the-scenes talent. In addition to the leads laying down their own vocals, Crazy Heart features contributions from T-Bone Burnett and Ryan Bingham (who won an Oscar for the song “The Weary Kind”). As someone who nearly cringes every time country is played, I can’t say I’m in a position to appreciate any of it.

When all is said and done, Crazy Heart’s tired tale of redemption has just enough juice to win audiences over. You’ll probably like it, but you won’t be able to shake the feeling you’ve seen it all before.

7.25/10

Crazy Heart is ample evidence that a great performance does not a great movie make. Scott Cooper’s film is slow-paced and conventional to the point of tired. There are numerous similarities to Tender Mercies, right on down to a shared cast member (Robert Duvall). And didn’t Mickey Rourke’s turn in The Wrestler make the “aging screwed-up has-been turns his life around” subgenre obsolete?

Nevertheless, this isn’t worth discarding. Bridges, in an Oscar-winning role, is excellent as the irrepressible Blake, a composite of Kris Kristofferson, Merle Haggard, and several lesser-known musicians. Gyllenhaal and Duvall (as Blake’s sympathetic friend) are rock-solid as voices of reason. Even Farrell is strangely credible as the young upstart Sweet.

Fans of country music will probably be enthralled by the behind-the-scenes talent. In addition to the leads laying down their own vocals, Crazy Heart features contributions from T-Bone Burnett and Ryan Bingham (who won an Oscar for the song “The Weary Kind”). As someone who nearly cringes every time country is played, I can’t say I’m in a position to appreciate any of it.

When all is said and done, Crazy Heart’s tired tale of redemption has just enough juice to win audiences over. You’ll probably like it, but you won’t be able to shake the feeling you’ve seen it all before.

7.25/10

Thursday, August 5, 2010

The Blue Star

In this sequel to Jim the Boy, a now-teenaged Jim Glass falls hard for Chrissie Steppe, the mysterious, reluctant girlfriend of local bigshot Bucky Bucklaw, who has left Aliceville to fight in World War II. With war tensions mounting and gossip spreading, Jim tries to figure out a way to win Chrissie over. Meanwhile, a long-ago romance between her mother and Jim’s protective Uncle Zeno threatens to complicate the situation even further.

The Blue Star marks the maturation of not only a character, but an author as well. While Jim the Boy gave Tony Earley a chance to introduce compelling characters and show off his North Carolina roots, there was something cloyingly winsome and provincial about that text. Thankfully, both The Blue Star and its protagonist have developed a bit of an edge. War, love triangles, teen pregnancy, and discrimination permeate this follow-up. Aliceville is still Aliceville, but Earley wisely decided to let more of the outside world in.

This isn’t to say that anyone will be confusing Earley with Palahniuk any time soon. The Blue Star’s plot and conflict are both conventional and familiar, as if ripped from some black-and-white melodrama. However, an infusion of colorful characters keeps it from being too mundane. Jim’s three bickering uncles are back, joined for this go-around by his juvenile friend Dennis Deane and his former flame Norma Harris (who, truth be told, seems a little too nice). Though absent from the actual narrative, Chrissie’s outlaw Cherokee father casts a dark shadow over the book, much the same way Jim’s bootlegger grandfather did the last go-around.

Earley carries over the practice of revealing out-of-narrative information through letters between the adults. It provides an interesting point of contrast for the story that’s being told through Jim’s eyes, but the effect it produces is akin to watching a movie where a lot of the big moments happen off-screen. Similarly, the book’s time structure is incredibly uneven. One day might span two chapters, while the next chapter might take place a month in the future.

The Blue Star’s title refers to a symbol hung in a window to indicate a member of a family is serving during wartime. The set-up for a continuation of Jim's adventures in a future book is insultingly obvious, but like everything else that’s wrong here (the simplicity, the familiarity, the cheese sentimentality), it works anyway. Above all else, Earley has created a character whose life you want to read about, and that is no small feat.

7.25/10

The Blue Star marks the maturation of not only a character, but an author as well. While Jim the Boy gave Tony Earley a chance to introduce compelling characters and show off his North Carolina roots, there was something cloyingly winsome and provincial about that text. Thankfully, both The Blue Star and its protagonist have developed a bit of an edge. War, love triangles, teen pregnancy, and discrimination permeate this follow-up. Aliceville is still Aliceville, but Earley wisely decided to let more of the outside world in.

This isn’t to say that anyone will be confusing Earley with Palahniuk any time soon. The Blue Star’s plot and conflict are both conventional and familiar, as if ripped from some black-and-white melodrama. However, an infusion of colorful characters keeps it from being too mundane. Jim’s three bickering uncles are back, joined for this go-around by his juvenile friend Dennis Deane and his former flame Norma Harris (who, truth be told, seems a little too nice). Though absent from the actual narrative, Chrissie’s outlaw Cherokee father casts a dark shadow over the book, much the same way Jim’s bootlegger grandfather did the last go-around.

Earley carries over the practice of revealing out-of-narrative information through letters between the adults. It provides an interesting point of contrast for the story that’s being told through Jim’s eyes, but the effect it produces is akin to watching a movie where a lot of the big moments happen off-screen. Similarly, the book’s time structure is incredibly uneven. One day might span two chapters, while the next chapter might take place a month in the future.

The Blue Star’s title refers to a symbol hung in a window to indicate a member of a family is serving during wartime. The set-up for a continuation of Jim's adventures in a future book is insultingly obvious, but like everything else that’s wrong here (the simplicity, the familiarity, the cheese sentimentality), it works anyway. Above all else, Earley has created a character whose life you want to read about, and that is no small feat.

7.25/10

Tuesday, August 3, 2010

Losing My Cool: How a Father's Love and 15,000 Books Beat Hip-hop Culture

Growing up in the 1980s and 1990s in suburban New Jersey, biracial Thomas Chatteron Williams fortifies his blackness by investing himself in hip-hop culture. This puts him at odds with his father, a proud black intellectual who had to fight for knowledge and respect. As Williams moves from New Jersey to Georgetown and swaps one set of friends for another, his notions about race and self take a series of dramatic turns.

Social critics are notorious blowhards and memoirists are notoriously self-indulgent, so a memoir by a social critic automatically has two strikes against it. Fortunately, Williams avoids the pitfalls of ponderous polemics and delivers an engaging tale of what it means to be black in the post-Civil Rights Era.

A Union County native (as am I), Williams captures the social geography of the Garden State to a T. Those who grew up in crime-ridden Newark and Irvington welcomed any opportunity to escape, while those who grew up in the suburbs wished they had the inner-city street cred. This moronic paradox underscores the necessity of Williams’ eventual flight to Georgetown and foreshadows his transformation from wannabe thug to perceptive young thinker.

Though an apostate of hip-hop culture, Williams eschews finger-pointing. His message is deeper and more complex than “bling bad, books good.” Instead, he convincingly makes the case that neither rappers nor their admirers (among whom he counts several friends) are inherently negative, but rather that young black men and women should not allow the shoes they wear and the music they listen to define them. It’s an important insight and it’s delivered by someone who’s been through it all.

8.25/10

Social critics are notorious blowhards and memoirists are notoriously self-indulgent, so a memoir by a social critic automatically has two strikes against it. Fortunately, Williams avoids the pitfalls of ponderous polemics and delivers an engaging tale of what it means to be black in the post-Civil Rights Era.

A Union County native (as am I), Williams captures the social geography of the Garden State to a T. Those who grew up in crime-ridden Newark and Irvington welcomed any opportunity to escape, while those who grew up in the suburbs wished they had the inner-city street cred. This moronic paradox underscores the necessity of Williams’ eventual flight to Georgetown and foreshadows his transformation from wannabe thug to perceptive young thinker.

Though an apostate of hip-hop culture, Williams eschews finger-pointing. His message is deeper and more complex than “bling bad, books good.” Instead, he convincingly makes the case that neither rappers nor their admirers (among whom he counts several friends) are inherently negative, but rather that young black men and women should not allow the shoes they wear and the music they listen to define them. It’s an important insight and it’s delivered by someone who’s been through it all.

8.25/10

Sunday, July 25, 2010

Extract

Trapped in a sexless marriage, flavor extract factory owner Joel (Jason Bateman) is looking for a way to change his life. He gets his chance when employee Step (Clifton Collins) loses a testicle in an industrial accident. Con artist Cindy (Mila Kunis) smells a lawsuit and sets herself up for a scam, catching Joel’s eye in the process. To rid himself of the guilt he would feel in pursuing her, Joel follows the advice of his friend Dean (Ben Affleck) and hires a pool boy (Dustin Milligan) to seduce his wife (Kristen Wiig).

It’s been more than a decade since Mike Judge shook up the white collar world with Office Space. He’s largely flown under the radar (2006’s Idiocracy never got a theatrical release) since then, but another workplace setting was bound to generate some buzz and invite some comparisons. It the case of Extract, these comparisons threaten to turn a perfectly watchable comedy into a dreadfully disappointing follow-up.

Extract is no Office Space. Though they share a writer/director (Judge), plot elements (a scam, pursuit of a dream girl), and a common theme (work sucks), it would do neither film justice to view Extract as an informal sequel. Not only does the newer film fail to measure up (less memorable characters, fewer laugh-out-loud lines), but the two films seem to be doing different things. Office Space was steeped in zeitgeist. Without the Y2K panic and the tech bubble, it couldn’t exist. Factory unrest, on the other hand, has more of a timeless quality. Further, the workplace is incidental to Extract. The movie is really about Joel’s lack of fulfillment and it would be much the same if he worked on a farm or at a car dealership.

Take away the comparisons and what you are left with is a serviceable, albeit conventional film. Bateman makes Joel likeable even when he’s doing dislikable things, and his attempts at rage and frustration are pretty amusing. The usually amusing Wiig plays it disappointingly straight as wife Suzie and Kunis continues to prove she isn’t much of an actress, but there are some good performances in minor roles. J.K. Simmons is delightfully dismissive as Joel’s factory cohort, while Beth Grant steals all her scenes as a lazy, racist, condescending, dim-witted employee. Don’t miss Gene Simmons as a money-hungry personal injury lawyer.

In a world where Office Space never existed, Extract would still probably be a letdown because it does not make full use of the talent involved. Nevertheless, it offers up a down-to-earth, if uneven and somewhat forgettable, of people behaving badly.

7/10

It’s been more than a decade since Mike Judge shook up the white collar world with Office Space. He’s largely flown under the radar (2006’s Idiocracy never got a theatrical release) since then, but another workplace setting was bound to generate some buzz and invite some comparisons. It the case of Extract, these comparisons threaten to turn a perfectly watchable comedy into a dreadfully disappointing follow-up.

Extract is no Office Space. Though they share a writer/director (Judge), plot elements (a scam, pursuit of a dream girl), and a common theme (work sucks), it would do neither film justice to view Extract as an informal sequel. Not only does the newer film fail to measure up (less memorable characters, fewer laugh-out-loud lines), but the two films seem to be doing different things. Office Space was steeped in zeitgeist. Without the Y2K panic and the tech bubble, it couldn’t exist. Factory unrest, on the other hand, has more of a timeless quality. Further, the workplace is incidental to Extract. The movie is really about Joel’s lack of fulfillment and it would be much the same if he worked on a farm or at a car dealership.

Take away the comparisons and what you are left with is a serviceable, albeit conventional film. Bateman makes Joel likeable even when he’s doing dislikable things, and his attempts at rage and frustration are pretty amusing. The usually amusing Wiig plays it disappointingly straight as wife Suzie and Kunis continues to prove she isn’t much of an actress, but there are some good performances in minor roles. J.K. Simmons is delightfully dismissive as Joel’s factory cohort, while Beth Grant steals all her scenes as a lazy, racist, condescending, dim-witted employee. Don’t miss Gene Simmons as a money-hungry personal injury lawyer.

In a world where Office Space never existed, Extract would still probably be a letdown because it does not make full use of the talent involved. Nevertheless, it offers up a down-to-earth, if uneven and somewhat forgettable, of people behaving badly.

7/10

Sunday, July 18, 2010

Murder by Death

Lured to the mansion of reclusive billionaire Lionel Twain (Truman Capote), the world’s greatest detectives assemble to dine and solve a mystery. They include wily Chinese Inspector Sidney Wang (Peter Sellers, parodying Charlie Chan), refined British couple Dick and Dora Charleston (David Niven and Maggie Smith, parodying Nick and Nora Charles), food-loving Belgian Milo Perrier (James Coco, parodying Hercule Poirot), hard-boiled San Francisco P.I. Sam Diamond (Peter Falk, parodying Sam Spade), and Englishwoman Jessica Marbles (Elsa Lancaster, parodying Miss Marple). Once the group is assembled, Twain reveals that a murder will occur at midnight and one million dollars will be awarded to whoever is able to solve it.

It’s hard to believe now that hordes of Scary Movie sequels and imitators have ruined their good name, but parody films were once both entertaining and respectable. Released in 1976, Murder by Death ranks alongside Airplane as the best of them. Directed by Robert Moore and penned by Neil Simon, this pastiche of Agatha Christie and Dashiell Hammett sends up literary and cinematic detectives with humor and style to spare.

The film boasts an impressive cast. In addition to the leads, a pre-Star Wars Alec Guinness serves as Twain’s blind butler, a debuting James Cromwell plays Perrier’s beleaguered chauffer, and Eileen Brennan is Diamond’s flirty secretary. Nobody is slumming here. Falk does hardboiled deadpan to perfection, waving a gun around, accusing everyone in sight of scandalous misdeeds and reaching obvious conclusions with gusto. Sellers gives his Asian stereotype character some sly wit, and frequently draws Twain’s ire for his refusal to use pronouns.

With lines like “One of us will be one million dollars richer, and one of us will be going to the gas chamber...to be hung!” the overall dialogue is some of the funniest ever crafted. It’s also a testament to everyone involved that the laughs increase as the plot becomes more twisted and convoluted.

The one strike against Murder by Death is its muddled letdown of an ending, the ambiguity of which the film itself acknowledges. Simon is clearly trying to make a statement about the genre he’s lampooning, but the negationism he displays here feels cheap and unsatisfying.

Fearlessly irreverent, deviously self-referential, and shamelessly over-the-top, Murder by Death walks the line between clever and stupid with a circus performer’s skill. When all is said and done and the body count totaled, the only true casualty is likely to be your boredom.

8/10

It’s hard to believe now that hordes of Scary Movie sequels and imitators have ruined their good name, but parody films were once both entertaining and respectable. Released in 1976, Murder by Death ranks alongside Airplane as the best of them. Directed by Robert Moore and penned by Neil Simon, this pastiche of Agatha Christie and Dashiell Hammett sends up literary and cinematic detectives with humor and style to spare.

The film boasts an impressive cast. In addition to the leads, a pre-Star Wars Alec Guinness serves as Twain’s blind butler, a debuting James Cromwell plays Perrier’s beleaguered chauffer, and Eileen Brennan is Diamond’s flirty secretary. Nobody is slumming here. Falk does hardboiled deadpan to perfection, waving a gun around, accusing everyone in sight of scandalous misdeeds and reaching obvious conclusions with gusto. Sellers gives his Asian stereotype character some sly wit, and frequently draws Twain’s ire for his refusal to use pronouns.

With lines like “One of us will be one million dollars richer, and one of us will be going to the gas chamber...to be hung!” the overall dialogue is some of the funniest ever crafted. It’s also a testament to everyone involved that the laughs increase as the plot becomes more twisted and convoluted.

The one strike against Murder by Death is its muddled letdown of an ending, the ambiguity of which the film itself acknowledges. Simon is clearly trying to make a statement about the genre he’s lampooning, but the negationism he displays here feels cheap and unsatisfying.

Fearlessly irreverent, deviously self-referential, and shamelessly over-the-top, Murder by Death walks the line between clever and stupid with a circus performer’s skill. When all is said and done and the body count totaled, the only true casualty is likely to be your boredom.

8/10

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

Twilight

In rural 1950s Tennessee, teenagers Kenneth and Corrie Tyler suspect their late bootlegger father didn’t receive a proper burial. After digging up his and other graves, they discover that well-to-do undertaker Fenton Breece has been defiling the dead. Armed with incriminating photos, they intend to blackmail him and ruin his reputation. Breece in turn hires Granville Sutter, a cunning, ill-tempered murderer, to recover the evidence. What follows is a cat-and-mouse chase through the barren backwoods.

About the worst that can be said for Twilight is that it has the misfortune of sharing its title with a series of poorly crafted vampire novels. But unlike Stephenie Meyer, William gay can actually write. His florid, intricate descriptions juxtaposed against plainspoken, quoteless dialogue call to mind Cormac McCarthy, but Gay is more innovator than imitator. Who else would be boldly transgressive enough to present a place where necrophiliacs and maniac killers are accepted as a matter of course?

Oozing with sinister tension, Twilight moves at a swift pace and builds character development along the way. Kenneth’s reluctance and fear make him a believable hero, while Breece is given a comic baffoonish quality to complement his depraved habits. The real star here though is Sutter. Like a white-trash Anton Chigurh, Sutter is self-aware, deceptively intelligent, and ruthlessly determined. One of the book’s more chilling moments occurs when he addresses a woman with a still-living husband as “widow Conkle,” knowing full well what he’ll do and how he’ll get away with it.

An unapologetically dark book, Twilight will alienate some with its cryptic downer of an ending. It remains, however, a well-crafted study of desperation and resolve, of Southern Gothic bogeymen and the decent folk who dare to defy them.

8.5/10

About the worst that can be said for Twilight is that it has the misfortune of sharing its title with a series of poorly crafted vampire novels. But unlike Stephenie Meyer, William gay can actually write. His florid, intricate descriptions juxtaposed against plainspoken, quoteless dialogue call to mind Cormac McCarthy, but Gay is more innovator than imitator. Who else would be boldly transgressive enough to present a place where necrophiliacs and maniac killers are accepted as a matter of course?

Oozing with sinister tension, Twilight moves at a swift pace and builds character development along the way. Kenneth’s reluctance and fear make him a believable hero, while Breece is given a comic baffoonish quality to complement his depraved habits. The real star here though is Sutter. Like a white-trash Anton Chigurh, Sutter is self-aware, deceptively intelligent, and ruthlessly determined. One of the book’s more chilling moments occurs when he addresses a woman with a still-living husband as “widow Conkle,” knowing full well what he’ll do and how he’ll get away with it.

An unapologetically dark book, Twilight will alienate some with its cryptic downer of an ending. It remains, however, a well-crafted study of desperation and resolve, of Southern Gothic bogeymen and the decent folk who dare to defy them.

8.5/10

Sunday, July 11, 2010

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

Thirty-six years after the disappearance of his grand-niece, elderly Swedish industrialist Henrik Vanger hires disgraced financial reporter Mikael Blomkvist to solve the mystery under the guise of writing a family history. Blomkvist is investigated – and later assisted – by Lisbeth Salander, an enigmatic young computer hacker. The more the Blomkvist uncovers, the more danger his discoveries put him in.

Published posthumously and now adapted into a movie, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo couldn’t have asked for a bigger profile. There’s a lot that can be said about it, good and bad, which already gives it a one-up on some titles topping the best-sellers lists.

First, the good: The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo has an engrossing central mystery and a number of tantalizing tangents (Blomkvist’s love life, Salander’s shady past, Swedish corporate malfeasance, etc.) that give it some breadth. The late author Steig Larsson was a political reporter and his adroitness as a researcher is evident here. The book has a tight chronology and a keen sense of verisimilitude with regard to contemporary Sweden.

While all this suggests Larsson was probably terrific as a nonfiction author, his debut mystery reveals him to be somewhat inept as a novelist. Structurally, this is a mess. The pacing is uneven, the point-of-view occasionally undergoes radical shifts, and the Salander thread is utilized inconsistently throughout. Instead of alternating Blomquvist and Salander chapters, she will disappear from the action for good-sized chunks of the novel, relegating her to the status of a secondary character despite her importance to both the plot and title.

Characterization on the whole is problematic. Blomkvist is neither unbelievable nor unsympathetic, but he comes off as too much of a Mary Sue (or would that be Marty Stungren, in this case), a blatant stand-in for the author. Salander is considerably less believable, and despite her evocative, contradictory nature, not as complex as she should be. She’s the Damaged Girl, through and through. The rest of the cast ranges from one-dimensional pastiches of the spoiled rich to genuinely compelling characters, such as Blomkvist’s beleaguered colleague/friend/lover.

The writing is similarly a mixed bag. There are some nice descriptions of the icy countryside, but plenty of placed where the prose felt stale. As this is an English adaptation of a Swedish book, it’s hard to tell what got lost in translation.

At 460 pages, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo isn’t a huge tome, but it often feels bloated. It’s talky, we get more Vanger family history and Swedish economic miscellanea than we really need to know, and there are too many character names to keep track of. All of this could be taken as Larsson shoring up his foundation, but it really detracts from the tension.

Lastly, Larsson’s anti-capitalist, anti-religious views cast a big shadow on the book. That wouldn’t be such a problem if they didn’t push plot developments into questionable directions. Larsson's determination to "get the bad guy" seems overly contrived in several instances.

For the most part, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo is entertaining reading. It’s refreshing to see a mystery that doesn’t take place in some dense urban landscape populated by characters cut from the same hard-boiled cloth (amusingly, Blomkvist reads a number of mysteries throughout the book). And as a debut novel, it shows a lot of promise. However, the aforementioned technical deficiencies are impossible to ignore. It’s a shame Larsson didn’t live long enough to follow his Millennium Trilogy up with more polished and tightly constructed efforts. As such, we’re left with an occasionally enthralling, occasionally infuriating mess of a mystery tinged with fascinating sociopolitical overtones.

6.75/10