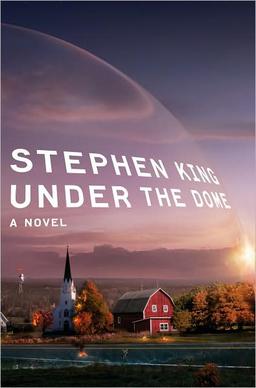

When a mysterious indestructible dome surrounds the small town of Chester’s Mill, Maine, a panic ensues. As the death toll rises and misfortunes multiply, the townsfolk increasingly divide their loyalties between Big Jim Rennie, a powerful local politician determined to keep order at all costs, and Dale Barbara, an Army veteran turned fry cook who has been recommissioned to find whatever is powering the dome and shut it down from the inside.

The latest from Stephen King is old hat for the veteran horror writer. He previously explored apocalyptic scenarios and small-town dynamics in works such as Cell, The Stand, and Needful Things. However, Under the Dome is no From a Buick 8 struggling to regain the glory of a prior Christine. This book is not only contemporary (President Obama is mentioned by name), but relevant as well. The incorporation of changing technologies, mistrust of government, and war-weariness into Chester’s Mill’s plight shows that King is very much in-sync with the problems and attitudes of today. Whether this will seem dated and inaccessible in 20 years is anyone’s guess.

At nearly 1100 pages, Under the Dome is not a light read. It is, however, a lean one. King’s pacing is excellent, as he continues to draw interest and build tension hundreds of pages in. There is very little here that felt superfluous or bloated.

Where this book falls short of greatness is in its characterization. On a macro level, King nails it. He employs his usual gift for Maine settings to construct The Mill as a fully realized place. As such, his characters, from Julia Shumway, the annoyingly persistent newspaperwoman to Peter Randolph, the dimwitted bureaucrat of a police chief, are wholly believable as representatives of that place. Taken as individual actors, however, they often falter. Rennie, for example, comes across as a Palpatine-type who has been waiting for an opportunity all along, while meth-addled Phil Bushey can be seen as his counterpart: a bad man waiting to do some good. By having these folks fit so neatly and transparently into the roles of savior, nemesis, etc., King deemphasizes the role that tragedy can have on a relatively normal human being.

Of course, this isn’t the only qualm. The language is slack in places, the feel-good ending felt clumsily executed, and we are transported to the point of view of a dog at one point. These are forgivable transgressions, given the length and scope of the novel, but they do tend to sap Under the Dome of its “epic” pretensions.

For King fans, Under the Dome is a difficult book to evaluate. Though full of completely new material, it is based on a concept King has attempted on and off since the 1970s. It reads neither like vintage King nor like a poor imitation/parody of his prior work. The best way to take it is probably to avoid comparisons and enjoy it for what it is: a compelling, vivid, flawed, politically astute, sometimes simplistic page-turner.

7.5/10

No comments:

Post a Comment