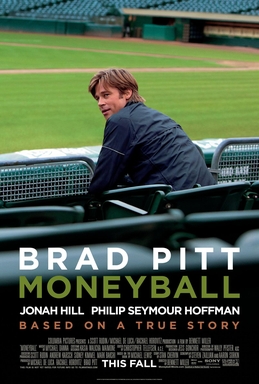

After the Oakland As are knocked out of the 2001 playoffs and lose key players through free agency, general manager Billy Beane (Brad Pitt) decides a new way of thinking is in order. To that end, he hires Peter Brand (Jonah Hill), a Yale-educated stats geek, and the two of them go about reshaping the roster. In doing so, they butt heads with old-school baseball men like manager Art Howe (Philip Seymour Hoffman), but as the season progresses, their radical thinking catches on.

Produced by Pitt, directed by Bennett Miller, and scripted by Aaron Sorkin from Michael Lewis’ influential book, Moneyball comes to the plate with an impressive pedigree. Still, it faces a sizeable limitation from the get-go: how do you make the story of a team that never won anything into a compelling cinematic narrative?

The answer is zeitgeist. Moneyball is set at a point in time where baseball’s biggest worry was not steroid abuse but financial disparities and contraction fears. In that context, the struggle of the As to stay afloat takes on new importance, and the stakes are raised. It is no longer just a baseball movie, but a fight-the-system resistance piece.

It also helps that Pitt comes out swinging as Beane. To be certain, some of his “maverick” moments seem manufactured, but Beane’s personal demons – choosing professional baseball over college, never succeeding as a player, struggling to be an adequate father – are fully realized. As for the rest of the lineup, Hill gets some funny lines as Brand (loosely based on the less nerdy Paul DePodesta), young Kerris Dorsey shows some musical ability as Beane’s admiring daughter, and Hoffman is solid if somewhat bland in a largely thankless, vaguely antagonistic role as Howe (a successful manager not cut out for 21st century baseball).

Compared to the book (and, presumably, reality), the film version of Moneyball takes a lot of liberties and cuts a lot of corners. No mention is made on-screen of the As then-emerging rotation (Tim Hudson, Barry Zito, and Mark Mulder), for instance. In terms of making the book filmable, however, the alterations are probably for the best.

Ultimately, Moneyball’s biggest weakness is the pesky intrusion of real life events. The film ends after the 2002 season with Beane turning down an offer from the Red Sox in order to remain in Oakland. Knowing that the As still haven’t made it to (let alone won) a World Series in the past 20 years, that Beane’s worship of on base percentage has not produced a particularly dynamic offense (to say the least), and that DePodesta flopped as general manager of the Dodgers goes against a lot of what this film stands for. And while such knowledge can’t be simply cast aside, it shouldn’t be enough to completely mar what is otherwise a quirky, compelling tale that transcends the ballpark.

8/10